The word “soonjung” translates literally as “pure heart”. The term was first discovered in October 1956 s in a magazine description of Jung Pa’s The Place Where The White Cloud Goes <흰 구름이 가는 곳>. In the 50s, there were three distinguishable branches of manhwa: hwalgeuk 활극 manhwa, myungrang 명랑 manhwa, and family 가족 manhwa.

Hwalgeuk manhwa narrated activities of a righteous hero much like a Robin Hood-like figure (rather than one with superpowers as seen in North American comics of the 1950s). Myungrang (“lively”) manhwa told light-hearted everyday comedy, with a focus on youth and children, and centered around a boy protagonist. Family manhwa sought to deliver moving inspiration, involving stories of the nuclear family, especially two parents and a young daughter. This led to young girls especially becoming fans of the genre. Soon, the genre began to cater to the tastes of the “elementary-school age” (approximately ages 6 to 12) female demographic. The coinage of the term “soonjung manhwa” cemented the popular definition of soonjung manhwa as “manhwa with a young girl protagonist”.

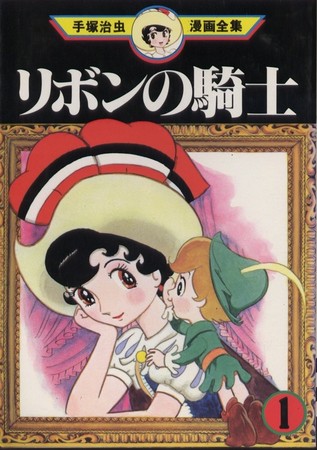

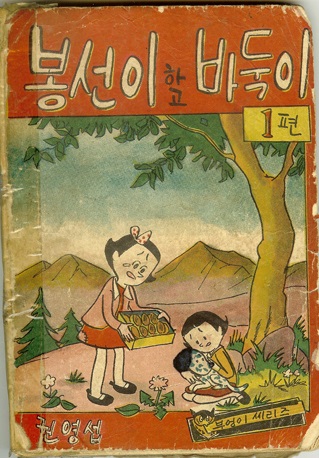

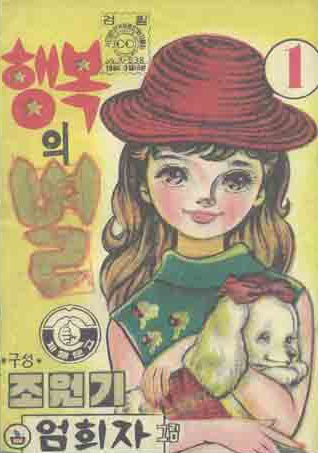

In 1953, Japanese mangaka Tezuka Osamu began to publish Princess Knight, heralding shojo manga, or manga for girls, as a serious genre itself. Tezuka’s protagonist had round faces and large eyes: the artificial and stylized beauty as reflected in the mangaka’s drawing became the standard for shojo manga. Korean soonjung manhwa of the 1960s was influenced by such aesthetics, marking a noticeable shift from the previous drawing style that did not include exaggerated body features. Kwon Young-Sub’s 1961 Bongseon and Baduk <봉선이와 바둑이>, which starred the innocent, pitiful heroine Bongseon, and Um Hee Ja’s 1964 Star of Happiness <행복의 별> shows Tezuka’s influence:

Over the 1960s and early 70s, male manhwa artists such as Bu Ho, Jo Ae-Ri, Jang Hee-Jung (all pen names) produced soonjung manhwa, but soon female artists such as Jang Eun-Ju, Min Ae-Ni, Lee Sung-Hee, Lee Mi-Ra, Choi Jin-Hee, and Um Hee-Ja began to produce cartoons as well. The women artists often wrote on topics heavier than those typically found in soonjung manhwa, and thus had better response from women readers than from elementary-school age girls. Um Hee Ja’s work is considered particularly exceptional for its refined storylines, methodical drawing, and coherent characters.

However, after the mid-1970s, soonjung manhwa as understood at that point in time disappeared almost overnight, and would not appear again until the early 1980s, in part due to the overwhelming popularity of imported shojo manga such as Kyoko Mizuki’s Candy Candy and Riyoko Ikeda’s Rose of Versailles.

In 1980, Hwang Mi Na would specifically attempt to create soonjung manhwa that was not coloured by the Candy aesthetic. This began an experimental movement by women writers who would expand the scope of manhwa narrative. By the late 1980s, the term soonjung manhwa would include both soneyo* manhwa, written primarily for girls, and yeoseong* manhwa, written primarily for women. In 1988, soonjung manhwa would reach a new landmark with the publication of Renaissance <르네상스>, the first monthly magazine devoted solely to soonjung manhwa.

Compiled from:

Choi, Yeol. The history of Korean cartoons 한국만화의 역사. Seoul: Yeolhwadang, 1995. ISBN 8930126030

Park, In-ha. Nuga Kʻaendi rŭl moham haenna 누가 캔디 를 모함 했나 : 박 인하 의 순정 만화 맛있게 읽기. Seoul: Sallim, 2000. ISBN 8952200438

Sohn, Sang-ik. Hanʼguk manhwa tʻongsa (1945 to present) 한국 만화 통사 : 문화사적 관점 에서 본 한국 만화 의 역사 와 이론 : 선사 시대 부터 1945년 까지. Seoul: Sigongsa, 1998. ISBN 8972598739

*Glossary:

sonyeo 소녀: translates to “girl”; from the same hanja/kanji as “shojo” in Japanese

yeoseong 여성: translates to “womanhood”