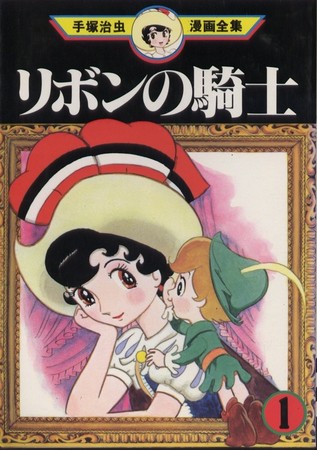

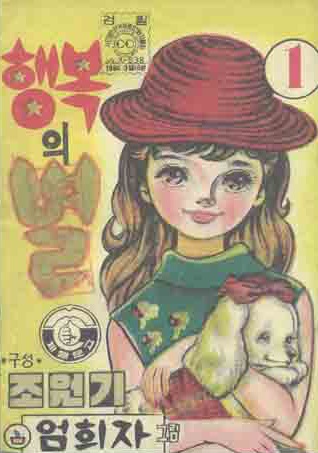

Examining Hani more closely, we see evidence of shift in content, thematic focus, and style from the shojo manga that dominated during 1970s.

The manhwa, which ran from 1985 to 1988, and was adapted into a 13-episode broadcast TV series in 1988, centres around Hani*, a 13-year-old girl whose mother died when she was a child. At the beginning of the series, her elderly nanny passes away, and as her father works as an architect overseas in the Middle East, Hani’s father’s new partner Ji-Ae sells Hani’s childhood house, citing that it is too big for Hani to live alone, and invites her to live together. Hani, a spunky teen obsessed with her mother’s death and despises Ji-Ae, becomes even more rebellious and leaves home altogether, moving into a decrepit one-bedroom apartment at the top of a residential building.

It is notable that Hani is centred around melodrama classically associated with female characters, and that the plot becomes increasingly more about Hani’s relationship with Ji-Ae towards the end of the series. However, the first half of the series is dedicated to Hani’s rise as sprint runner.

Hong Doo-Kkae, former runner and Hani’s new homeroom teacher, discovers her talent and starts a track team to coach Hani. Hong Doo-Kkae, like Hani, is himself a marginalized character, and is rarely taken seriously by his students and coworkers, at first impression. Despite his ironically handsome appearance that intentionally recalls the feminine male “prince charming” archetype of 1970s shojo manga, he is a poor, orphaned bachelor with a tacky sense of humour, who lives in a room rented behind a grocery store, and is often mistaken for the local blue-collared worker.

Recruited into the newly formed track team are Chang-Soo, a boy from an affluent family who develops a crush on Hani despite their initial conflict, and Yang-Gil, a boy from an impossibly impoverished family in which the 13-year-old boy is the main breadwinner. Hani, once subjected to disdain and belittlement from teachers, school principal, and students, become a source of inspiration when she breaks the record for the 100m sprint in a city competition, and advances to an international race in Australia.

Halfway through the narrative, she becomes almost permanently injured at the ankle, and must retrain as long-distance runner rather than sprint runner. Through her physical hardships, support received from her group of exceptionally eclectic friends, and the return of her father from overseas, her uncontrollably wild rebelliousness transforms into a more reflective gratitude, a letting go of her obsession with her mother’s death, and self-awareness.

Unlike Candy Candy, which is also a coming-of-age tale of a teenage girl, Run Hani is squarely situated in the place it was produced in. Hangeul (the Korean alphabet) is used profusely on school plaques, apartment building signs, and grocery store billboards, marking a difference from Candy’s orphanage home marked PONY’S HOME in English alphabet in the very beginning of the manga.

Characters are Korean, except for the athletes that Hani competes against in her races and sometimes interacts with. The origins of the foreign characters are made straightforward as sports commentators call out their names and nationality at the beginning of each race.

In one of the first few episodes, Hani and Hong Doo-Kkae makes from scratch kimchi, a representative Korean food, in a meagre urban kitchen, and has to scrap money to buy rice to eat the kimchi with afterwards. In contrast, in the second episode of the Candy animated series, she and her friend Annie feast on meat and vegetables on kebabs cooked in an outdoor barbeque of a ranch belonging to a wealthy man in Michigan. Hani is decidedly Korean, recalling the artist’s statement that he primarily looks to his immediate sources for inspiration when writing manhwa.

Male characters in the series hardly resemble the feminine, elegantly dressed characters of Candy and Rose of Versailles. The two that come the closest visually to the feminine male archetype are Hong Doo-Kkae and Hani’s father. However, as earlier mentioned, Hong Doo-Kkae’s handsome appearance is radically undermined by his tacky humour and unstylish mannerisms that most other characters find laughable. He is depicted with unkempt facial hair, and wears the same track outfit (often with plastic flip flops) throughout the story.

Hani’s father is totally absent for the first half of the narrative, and when he appears, he is injured and bandaged around the eyes, and appear only as under medical care, until the very end when he recovers enough to witness Hani taking her last steps of the marathon. It is interesting that the character closest to giving off a Western or European association is Ji-Ae, Hani’s father’s new romantic partner. A television personality, she is dressed in power suits and almost always wears a beret and sunglasses, highly in contrast to Hani’s passed mother, who is always depicted in hanbok, or traditional Korean dress, in Hani’s memories.

In the end of the narrative, Hani herself foresees that she will be able to let go of her mother’s death if she completes the marathon, and also warms up to Ji-Ae, realizing that much of her blinding hatred towards Ji-Ae has been uncalled for. Ji-Ae becomes a mildly helpful figure to Hani, despite the clear awkwardness between the two. Ji-Ae, who herself lost her mother as a child and had to welcome a new mother figure into her life, taunts Hani in a way that she knows will encourage Hani to continue to re-train as long-distance runner.

If Hani were to be a symbol for the Korean people, we see in the manhwa a young nation still traumatized by the death of her mother, or the end of the unified Korea, after the Korean War in the mid-1950s. Hani’s obsession with her mother and rejection of outside authority leads her to stardom but also violent injury to herself, when she tries to go too fast too suddenly. She must re-train to get back up on her feet, and learn to run from something other than the uncontrolled anger and sadness she feels: thus, she must maintain internal composure while competing. Perhaps Lee Jin-Ju alludes that the nation can only truly go forward when the endless lamentation and forced and erratic strength is transformed to something more poised and balanced.

When Hani, as the very last athlete in the race, takes her very last steps of the five-hour marathon, she also takes gradual steps to making peace with what was. Her stream of thoughts tell us that she runs for herself and those currently around her who have helped her to re-train, rather than for the memory of her mother and the emotional baggage she has clung onto. It is important that we only see a figurative victory at the end of the story, as we see Hani take her last agonizing steps, and do not see her in actual victory or in celebration. Lee Jin-Ju perhaps subtly implies that a true win does not entail a tangible “end goal” and that learning to become resilient itself is the victory.

Glossary

*Hani: the name is stylized after the English word “honey”, and is also a play on words as Ha is a common Korean surname; “Hani” allows the protagonist to go by a (catchy, iconic) mononym